Even now when flight schedules are significantly reduced airlines will want to ensure the best efficiency of their operational fleets. In fact with revenues diminished by the restrictions introduced to combat the Covid-19 pandemic you could argue that they are even more important now than before as airlines look to keep costs to a minimum during a time that demand remains diluted.

But it is no longer about just getting passengers on an aircraft as quickly as possible, but doing this in the safest manner possible. When it comes to boarding or disembarking there are so many variables to consider with the process - the aircraft type, the flight load, airport infrastructure, using an airbridge or remote stand, using multiple doors are just some factors. Then, of course, there are the economic influences on the process -frequent flyers, those that have booked premium classes of travel or an ancillary option of boarding the aircraft ahead of others.

In general a boarding group approach has been the most common based on the area of the cabin you are seated. It may not be the most efficient but is the easiest to manage. LCCs prefer the random approach but boarding via the front and back of the aircraft, a process that studies suggest can deliver an efficiency enhancement of around a quarter. Many believe an outside to inside option - window to aisle - is the fastest, but that will need a changing consumer mindset to become commonplace.

Right now many airlines are adopting a single forward door loading in a rear to front approach developed to minimise potential contact points as passengers pass down an aircraft. It seems to make sense on paper.

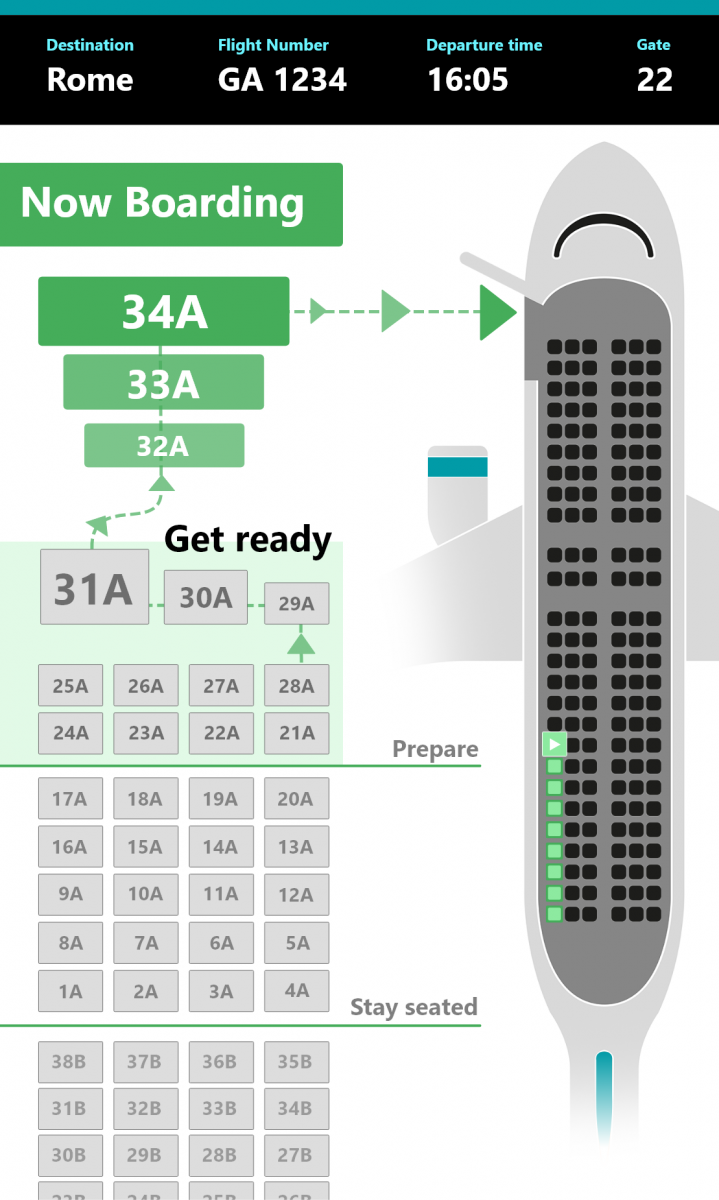

In fact, similar methods have been trialled ahead of the current Covid-19 public health crisis. One example was in Oct-2019 at London Gatwick where the UK developed what became known as 'bingo boarding' at one of its gates for a two week period as part of an experimentation of flexible boarding patterns.

Instead of the traditional tannoy announcement informing which group of rows were boarding, seat numbers were displayed on a digital screen as the aircraft was boarded from window seats first, starting at the back, followed by middle then aisle seats.

It estimated that double-digit efficiency gains could be achieved from this process, but it also offers what appears to be obvious welfare benefits for passengers. But, that all disappears if passengers aren't alert for their boarding slot. If they miss their time do they simply have to wait until the end or can they board when they wish?

The boarding and disembarkation process is one that can infuriate travellers as they get held up in the aisles while passengers mess around with their coats and baggage. With overhead locker space at a premium boarding the aircraft as early as possible had become a preferred approach.

This may not be a problem while demand remains reduced, but some airlines are already reporting growing loads and some routes will be particularly busy. And contrary to widespread belief new academic research now indicates that adopting a random approach to boarding could actually reduce potential exposure rates by about 50% and is actually more effective in reducing potential infection risk than keeping middle seats vacant.

These findings are still in the process of being peer reviewed, but if confirmed, "they suggest that airlines should either revert to their earlier boarding process or adopt the better random process," according to Ashok Srinivasan of Florida State University, who co-authored the paper alongside Dr. Sirish Namilae, associate professor of Aerospace Engineering at aviation leader Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University, and other researchers.

Dr Namilae, whose prior work at Embry-Riddle has shown how pedestrian dynamics through airport security lines and during aircraft boarding and deplaning may impact infection rates, first began researching how viruses spread during the Ebola outbreak of 2017. Key to the research, he said, is in understanding how molecules travel.

"While back-to-front boarding has been instituted by some airlines to try and reduce contact between people, our simulations show that high-density clusters can form as people stow their luggage," said Dr Namilae.

Contact points in the study are defined by a "person-minute" of contact, or the number of minutes a person stands within six feet of proximity from someone else while boarding an aircraft. The more of these person-minutes were recorded in each of the team's roughly 16,000 simulations - simulations that varied the parameters of walking speed, proximity, number of people, etc., then ran the data through a Frontera supercomputer - the higher the infection probability.

These simulations were then tested through several boarding patterns: front-to-back, back-to-front, through six boarding zones and random boarding through one zone. "It turns out, the one-zone, random boarding model eventually results in a lower number of contacts," Dr Namilae said. "Other patterns tend to increase the time a passenger waits in close proximity to fellow travellers."

In simulations that assume full capacity of an Airbus 320, 43,000 person-minutes of contacts were recorded in the random boarding model compared to 60,000 person-minutes for six-zone boarding, 90,000 person-minutes for back-to-front boarding and even higher for the front-to-back boarding pattern.

"Our analysis indicates that airlines that changed to a back-to-front boarding policy erred, exposing passengers to substantially higher infection risk than their original procedures," said Mr Srinivasan. "This result shows that good intention is not a substitute for good science when it comes to determining policies."

The policy of some airlines to keep middle seats unoccupied, though, he added, proved effective in significantly reducing infection risk - as proven by the team's simulations, which included scenarios in which middle seats were left occupied or empty. While demand levels are low that is fine, but how long airlines can afford to fly with empty seats as demand picks up is uncertain.

Economics are a consistent consideration in these simulations, acknowledged Dr Namilae. Transporting passengers in multiple smaller aircraft, for example, was shown to pose a lower risk of infection to passengers than if one larger aircraft was used. The key, however, is finding a middle ground - and for Dr Namilae and his team, that conversation has to begin with the boarding process.

"There's evidence of a lot of diseases, such as tuberculosis and SARS, being transmitted on airplanes and in air travel," he said. "Boarding is one of the critical aspects of air travel that contributes to the spread of diseases. Any steps we can take to reduce the spread would help."