Summary:

- Finland's state ownership of airports "works well" according to Finavia's CEO and the same seems to be true of other Nordic countries;

- There is little private interest in airports across the region, perhaps explained by their being a small number of large and profitable primary airports supporting a much larger number of widely scattered unprofitable secondary ones.

- Geographical isolation of many airports is a major factor and both private ownership and concession models will be found wanting across the region

He added, "in that perspective, in Finland [state ownership] works quite well. In many cases the concession model is good but there have to be some reasons to go for that." Finavia operates 21 of the 28 commercial airports with municipalities accounting for the remainder. There are no privately owned ones. There was some talk of privatisation and foreign investment five or six years ago but nothing came of it.

MAP - The Nordic countries refer to Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden, including their associated territories (Greenland, the Faroe Islands and the Åland Islands) Source: Google

Source: Google

That position is typical of the one taken within the Nordic countries as a whole. There is little private interest in airports while, for example, the UK's airports are largely privately controlled (though there has been some reversion to public control), France has a privatisation programme and there are partially privatised airports in Germany.

In Sweden, Swedavia, the state operator has less overall control, with 10 airports under its control, including those at the main cities of Stockholm, Gothenburg and Malmö. It does not operate all of them and some of the others, including those in local ownership that are members of an independent group, have been targeted for privatisation. Even so, private activity has been limited.

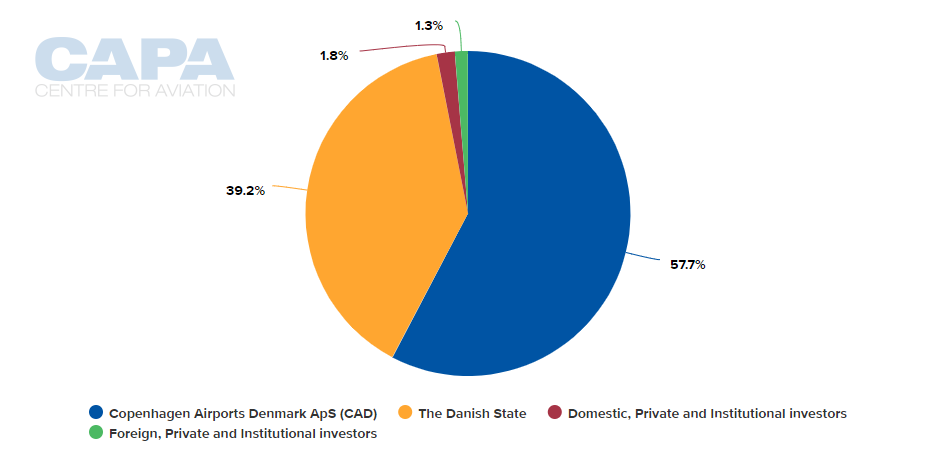

Denmark is unusual in that Copenhagen Airports, which operates Kastrup and Roskilde airports, is publicly listed and Copenhagen Airports has been a foreign investor. Otherwise its owners are pension and investment funds from Canada and Australia.

CHART - Copenhagen Airports, which operates Kastrup and Roskilde airports, is publicly listed and Copenhagen Airports has also been a foreign investor Source: CAPA - Centre for Aviation

Source: CAPA - Centre for Aviation

Billund Airport started as a private airport to serve Legoland but is now owned by eight municipalities. In late 2016 a replacement airport for Aarhus, currently owned by five municipalities, was discussed together with the attraction of private funding but nothing came of it.

In Iceland, Keflavik, Reykjavik and the other airports, scattered around the country, come under the remit of state operator Isavia. There has been some talk of privatisation but with the tourism bubble having burst that driver may diminish in importance. Neither Greenland nor the Faroe Islands (Danish dependencies) have private commercial airports.

There has been privatisation activity in Norway and state operator Avinor, like its Finnish and Icelandic counterparts, has looked into the advantages and disadvantages of privatisation. 60 km (40 miles) south of Oslo the Moss Rygge Airport, which was once partly owned by Copenhagen Airports, was in the ownership of private companies and the Østfold municipality until its closure in Nov-2016. It was subsequently acquired by a distress investment company, Jotunfjell Partners, which intends to reopen it to commercial traffic in 2019.

Meanwhile, another airport to the south of Oslo, Sandefjord Torp, which has benefitted from Moss Rygge's closure, counts a private investment group amongst its shareholders.

Together, there is only a small amount of activity amongst five countries and their dependencies. Part of the reason for that is the spirit of social enterprise that exists in the Scandinavia; the Nordic Model as it is known. While that model commits to private ownership there are caveats, and one of them is that a partnership between employers, trades unions and the government is paramount, in order to protect workers' rights. Such a partnership does not always sit easily with privatisation though.

The major reason is that in all cases except perhaps Denmark there are a small number of large and profitable primary airports supporting a much larger number of widely scattered unprofitable secondary ones. The former sustain the latter financially.

Privatising the larger ones, while it would provide an immediate financial boost to the government which could be spent on infrastructure improvements at the smaller ones (though that might not happen, it could be spent elsewhere), would remove that 'prop' from the smaller ones over time, potentially leading to closure and community isolation. At the same time it might well not be possible to privatise all the airports as few investors would wish to commit resources to loss-makers for any length of time, however they were packaged up.

Operating airports under concession comes up against the same barriers. How will the concessionaire make money out of the remote airports? Until a new model is produced which gets around this sticking point, this aviation Nordic Model looks sure to continue.